C++20 Coroutines and io_uring - Part 1/3

As part of my job I have to deal with quite heavy I/O loads. Multiple times I’ve jumped into a fighting ring facing challenges that demand me to perform thousands of I/O operations in the most efficient way possible. And I haven’t always won. This has directed my attention to more powerful weapons, weapons like io_uring. io_uring is a new asynchronous I/O API in the Linux kernel which offers efficiency and scalability never seen before. With coroutines accepted into the c++20 standard and matured enough implementations at my disposal, I had all I need to forge the ultimate weapon, or at the very least an irresistible hobby project.

In this series of posts we’ll write a program that reads lots of files stored on disk using Linux io_uring and C++20 coroutines. The main motivation comes from the fact that there are lots of in-depth resources for both io_uring and C++20 coroutines, but practically nothing showing how to combine both. We will discover that asynchronous I/O and coroutines go as well together as bread and butter.

Before we start look at the drawing my girlfriend did for me, it shows io_uring coexisting harmonically with coroutines:

The series will be split into three parts. In the first part we will solve the problem using io_uring only. In the second part we will remodel the implementation on top of C++20 coroutines. In the third part we will optimize the program by making it multi-threaded, this will reveal the true power of coroutines.

|  |

Async I/O ❤ Coroutines

Asynchronous I/O, as opposed to synchronous I/O, describes the idea of performing an I/O operation without blocking the calling thread. Instead of waiting until the operation finishes, the thread is released immediately and can do other work while the requested operation is being performed in the background. After a while the calling thread (or some other one) can come back and collect the results of the requested operation. Its like when you tell your pizza guy: “put a margherita in the oven, I’ll go grab something from the pharmacy and will be right back”.

Asynchronous I/O can be a lot more efficient than synchronous I/O, threads don’t need to wait for resources to become available, but at the same time it makes programs more complex. Programs need to work, well, asynchronously, they must remember to pick up the margheritas they ordered.

Coroutines allow us to write asynchronous code as if it was synchronous. If you write a coroutine that loads a file from disk, it can suspend execution and return to the caller while the file is being loaded, and resume once the data is available. All written as if it was a good-old synchronous call.

Combining asynchronous I/O and coroutines allows us to write asynchronous programs without actually writing asynchronous code. The best of both worlds.

Goals

In this post series we will be writing a program that reads and parses hundreds of wavefront OBJ files from disk.

Its important to understand the distinction between reading and parsing. Reading denotes the action of loading the contents of a file from disk into a memory buffer. Parsing means taking the data in the buffer and transforming into into a data structure that makes sense to the application.

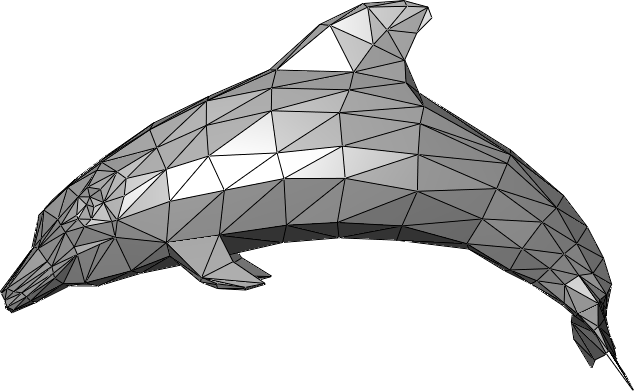

An OBJ is an ASCII file that describes the geometry of one or more 3D triangular meshes. The file encodes information like the triangles that make up the mesh, their vertices, colors, etc. Parsing an OBJ file means converting its ASCII representation into a C++ objects that has a convenient API for accessing the meshes attributes.

source: wikipedia

For parsing the OBJ files we will use a library called tinyobjloader. It receives a string containing the contents of the OBJ file and parses it into a ObjReader object:

std::string obj_data = // the contents of the OBJ file

tinyobj::ObjReader reader;

reader.ParseFromString(obj_data);

We can use the API of reader to access the attributes of the shapes defined in the file. For example, to list how many shapes are defined in the file you can do the following:

std::cout << reader.GetShapes().size() << '\n';

Ground Work

First of all let’s lay down some ground work by defining some basic abstractions that will make our implementation easier and safer.

We will be dealing with files, so we write an RAII class that manages a read-only file:

class ReadOnlyFile {

public:

ReadOnlyFile(const std::string &file_path) : path_{file_path} {

fd_ = open(file_path.c_str(), O_RDONLY);

if (fd_ < 0) {

throw std::runtime_error("Fail to open file");

}

size_ = get_file_size(fd_);

if (size_ < 0) {

throw std::runtime_error("Fail to get size of file");

}

}

ReadOnlyFile(ReadOnlyFile &&other)

: path_{std::exchange(other.path_, {})},

fd_{std::exchange(other.fd_, -1)},

size_{other.size()} {}

~ReadOnlyFile() {

if (fd_) {

close(fd_);

}

}

int fd() const { return fd_; }

off_t size() const { return get_file_size(fd_); }

const std::string &path() const { return path_; }

private:

std::string path_;

int fd_;

off_t size_;

};

Quite simple, it opens a file in read only mode and closes it on destruction. We do some (very clumsy) error handling and implement a move constructor, so that the type can be stored inside some STL containers like std::vector.

Another type we will use a lot is Result:

struct Result {

tinyobj::ObjReader result; // stores the actual parsed obj

int status_code{0}; // the status code of the read operation

std::string file; // the file the OBJ was loaded from

};

This is the final result of parsing of an OBJ file, it contains the final OBJ object, the corresponding file path, as well as the status code of the read call.

The goal of our program is to load a list of OBJ files and return a std::vector<Result>.

First Attempt: A Trivial Approach

Now that we have laid down some ground work we can continue with the main dish. As usual, let’s start with the easiest possible implementation: a single-threaded blocking file loader.

Result readSynchronous(const ReadOnlyFile &file) {

Result result{.file = file.path()};

std::vector<char> buff(file.size());

read(file.fd(), buff.data(), buff.size()); // blocks until finished

readObjFromBuffer(buff, result.result);

return result;

}

readSynchronous receives a file, loads its contents into a buffer and parses the data in the buffer into an OBJ object. readObjFromBuffer wraps around tinyobjloader and initializes the result member of Result.

void readObjFromBuffer(const std::vector<char> &buff, tinyobj::ObjReader &reader) {

auto s = std::string(buff.data(), buff.size());

reader.ParseFromString(s, std::string{});

}

Unfortunately, tinyobjloader doesn’t support std::string_view so we are forced to make a copy of the buffer. Maybe I’ll open a PR in the next days.

All we need to do now is call readSynchronous for every file:

std::vector<Result> trivialApproach(const std::vector<ReadOnlyFile> &files) {

std::vector<Result> results;

results.reserve(files.size());

for (const auto &file : files) {

results.push_back(readSynchronous(file));

}

return results;

}

This is easy, but slooow. The read syscall blocks the calling thread until the data has been read into the buffer. And I mean the thread, there is only one thread that waits for I/O and does the parsing for all files. We can’t start processing the next file until the parsing of the previous one finished!

The context switches between user and kernel mode are not harmless either, every time that we call read we switch into kernel mode. If we load hundreds of files we will have hundreds of context switches between user and kernel space.

We can do better.

Next Attempt: Thread Pool

I know what you are thinking, just parallelize!

std::vector<Result> threadPool(const std::vector<ReadOnlyFile> &files) {

std::vector<Result> result(files.size());

BS::thread_pool pool;

pool.parallelize_loop(files.size(),

[&files, &result](int a, int b) {

for (int i = a; i < b; ++i) {

result[i] = readSynchronous(files[i]);

}

})

.wait();

return result;

}

Here we are using bshoshany’s thread-pool library to run individual iterations of the for-loop in parallel. Every thread receives a fixed number of iterations, denoted by the range [a,b). You can also use something like openMP, or std::async, the idea is the same.

This is better, even when the threads are still being blocked on read and a system call is performed per file, multiple files are being processed in parallel. The overhead in terms of code changes is very small, and it opens further optimization opportunities: we can for example allocate a single buffer per thread that can be reused by multiple files.

For many applications this approach is more than sufficient, but imagine that you developing a web server, listening to thousands of socket connections at once. Would you create a thread per socket? Probably not. What you need is a way of telling the OS: “Look, I’m interested in these sockets, let me know when any of them has any data to be read, I’ll continue with my day”. What you need is asynchronous I/O.

Enter io_uring

io_uring is a new asynchronous I/O API available in the Linux kernel (version 5.1 upwards). This is not the first API of its kind, there are other options available in the kernel, like epoll, poll, select and aio, all with their issues and limitations. io_uring aims to start a new page and become the standard API for all asynchronous I/O operations in the kernel.

The API is called io_uring because its based on two ring buffers: the submission queue and the completion queue. The buffers are shared between user code and the kernel and writing to or reading from them does not require system calls or copies.

The idea is simple: user code writes requests into the submission queue and submits them to the kernel, the kernel consumes the requests in the queue, performs the requested operations, and writes the results into the completion queue. User code can asynchronously retrieve the completed requests from the queue at a later point.

The raw API of io_uring is a little complex, this is why programs usually use a wrapper library called liburing (created by Jens Axboe, original author of io_uring), which extracts most of the boilerplate away and provides convenient utilities for using io_uring.

Parsing OBJs with liburing

We will now implement our program using liburing.

First of all we define a thin wrapper RAII class that initializes an io_uring object and frees it upon destruction:

class IOUring {

public:

explicit IOUring(size_t queue_size) {

if (auto s = io_uring_queue_init(queue_size, &ring_, 0); s < 0) {

throw std::runtime_error("error initializing io_uring: " + std::to_string(s));

}

}

IOUring(const IOUring &) = delete;

IOUring &operator=(const IOUring &) = delete;

IOUring(IOUring &&) = delete;

IOUring &operator=(IOUring &&) = delete;

~IOUring() { io_uring_queue_exit(&ring_); }

struct io_uring *get() {

return &ring_;

}

private:

struct io_uring ring_;

};

io_uring_queue_init initializes an instance of io_uring with a given queue size (this is the size of the ring buffers of the completion and submission queues). io_uring_queue_exit destroys an io_uring instance.

Let’s now try to implement our OBJ loader using liburing.

The implementation must consist of two parts: first we must push the file read requests to the submission queue. Second, we have to wait for completion requests to arrive at the completion queue and parse the contents of the buffer as they come.

std::vector<Result> iouringOBJLoader(const std::vector<ReadOnlyFile> &files) {

IOUring uring{files.size()};

auto buffs = initializeBuffers(files);

pushEntriesToSubmissionQueue(files, buffs, uring);

return readEntriesFromCompletionQueue(files, buffs, uring);

}

We start by creating an io_uring instance with enough queue capacity to hold an entry for each file. Next we allocate the buffers, one per file.

pushEntriesToSubmissionQueue writes the submission entries into the submission queue:

void pushEntriesToSubmissionQueue(const std::vector<ReadOnlyFile> &files,

const std::vector<std::vector<char>> &buffs,

IOUring &uring) {

for (size_t i = 0; i < files.size(); ++i) {

struct io_uring_sqe *sqe = io_uring_get_sqe(uring.get());

io_uring_prep_read(sqe, files[i].fd(), buffs[i].data(), buffs[i].size(), 0);

io_uring_sqe_set_data64(sqe, i);

}

}

io_uring_get_sqe creates an entry in the submission queue, sqe. We can now set the contents of the submission entry with io_uring_prep_read, which specifies that we want the kernel to read the contents of the file pointed to by files[i].fd() into the buffer buffs[i].

One can also append user data to the submission entry with io_uring_sqe_set_data. This is data that is not used by the kernel but is just copied into the corresponding completion entry of the current request. This is important in order to differentiate which completion entry corresponds to which submission entry. In this case we just write the index of the file, which we can use to reference back when the read operation completes.

After we have written all the submission entries into the queue its time to submit them to the kernel and wait until they start appearing in the completion queue. Once completion entries appear, we can read the corresponding buffers into OBJ files:

std::vector<Result> readEntriesFromCompletionQueue(const std::vector<ReadOnlyFile> &files,

const std::vector<std::vector<char>> &buffs,

IOUring &uring) {

std::vector<Result> results;

results.reserve(files.size());

while (results.size() < files.size()) {

io_uring_submit_and_wait(uring.get(), 1);

io_uring_cqe *cqe;

unsigned head;

int processed{0};

io_uring_for_each_cqe(uring.get(), head, cqe) {

auto id = io_uring_cqe_get_data64(cqe);

results.push_back({.status_code = cqe->res, .file = files[id].path()});

if (results.back().status_code) {

readObjFromBuffer(buffs[id], results.back().result);

}

++processed;

}

io_uring_cq_advance(uring.get(), processed);

}

return results;

}

}

First we call io_uring_submit_and_wait, which submits all entries to the kernel and blocks until at least one completion request has been pushed into the completion queue.

Once we have completion entries in the queue we can start processing them. io_uring_for_each_cqe is a macro defined in liburing whose body gets executed for every completion entry in the completion queue.

This is what we must do after a completion entry arrives:

- get the id of the file this completion entry corresponds to. This is the same id we wrote into the corresponding submission entry.

- Write the status code into the

Resultobject. This is the status code of thereadoperation performed by the kernel. - If the read was successful parse the OBJ from the buffer into the

Resultobject.

Finally we can liberate some space in the submission queue as we have processed some completion entries. For this we use io_uring_cq_advance, which does nothing more than moving head of the ring buffer back by n elements, making room for more entries.

Closing Thoughts

The big advantage of the io_uring implementation is the substantial reduction of syscalls performed. In fact, using strace we can see that the io_uring implementation has 512 less system calls than in the synchronous case, this is due to the read syscalls:

> strace -c -e read -- ./build_release/couring --trivial

Running trivial

Processed 512 files.

% time seconds usecs/call calls errors syscall

------ ----------- ----------- --------- --------- ----------------

100.00 0.000591 1 517 read

> strace -c -e read -- ./build_release/couring --iouring

Running iouring

Processed 512 files.

% time seconds usecs/call calls errors syscall

------ ----------- ----------- --------- --------- ----------------

100.00 0.000053 10 5 read

Instead of performing one read syscall per file, we perform none. Note that reading and writing to io_uring queues is not a syscall and doesn’t involve a context switch.

Our io_uring implementaion approach still has some issues, though. First, the code is substantially more complex than the synchronous case, we no longer have a single synchronous function that reads and parses an OBJ file, but rather a program that writes to a queue and then polls it. This makes is very hard to extend.

Second, our program is CPU-bound. As some profiling shows, most of the time is spent parsing the OBJs:

% cumulative self

time seconds seconds

31.25 0.05 0.05 tinyobj::tryParseDouble(char const*, char const*, double*)

18.75 0.08 0.03 tinyobj::LoadObj(tinyobj::attrib_t*, std::vector<tinyobj::shape_t, std::allocator<tinyobj::shape_t> >*, std::vector<tinyobj::material_t, std::allocator<tinyobj::material_t> >*, std::__cxx11::basic_string<char, std::char_traits<char>, std::allocator<char> >*, std::__cxx11::basic_string<char, std::char_traits<char>, std::allocator<char> >*, std::istream*, tinyobj::MaterialReader*, bool, bool)

12.50 0.10 0.02 allDone(std::vector<Task, std::allocator<Task> > const&)

12.50 0.12 0.02 tinyobj::parseReal(char const**, double)

6.25 0.13 0.01 tinyobj::parseReal3(float*, float*, float*, char const**, double, double, double)

...

The parsing of the OBJ files still happens on a single thread. While processing the submission entries happens on a thread pool inside the kernel, consuming the completion entries happens in a single thread in user space. Is clear that we must parallelize the parsing path.

In the next parts of the series we will try to solve these problems. Continue with part 2.